What Breaks & What Remains

Who would believe the ice made music before it made death?

The ice sang. Not cracked—sang. A rising note beneath his feet, pure as church bells but somehow wrong. Caspar David would tell no one this. Who would understand that beauty and death arrived together, inseparable as breath and air?

January 1787. The Baltic winter had turned the sea to land. The Friedrich boys walked where fish should swim.

"Johann," he said, "we should go back."

Johann Christoffer laughed, eleven years old and fearless. "But look how the light bends through it."

And it was true. The winter sun caught in the frozen surface, transforming ordinary ice into something sacred. In that moment Caspar David understood what made cathedrals holy—not stone but light moving through what seemed solid.

Johann stepped forward, pointing toward the distant harbor. "Just a little further."

The singing changed its tone. Lower, then a sigh, then silence before the sound of breaking.

Memory would fragment here. Johann's red cap bright against white sky. The sudden dark water. The way his brother's face showed not fear but surprise, as if death were simply an unexpected guest at dinner.

Caspar David lunged forward on his belly, arms outstretched. The distance between them never closed. The ice held him but not his brother.

Johann surfaced once. Their eyes met across impossible distance. Johann said something Caspar David couldn't hear. Then the water took him completely.

Later, they asked questions. "Did he fall through trying to save you?" His father, voice thick with grief and accusation. Caspar David said nothing. Let them believe what would hurt less.

The truth lived in his bones—how he'd walked on ice that sang while his brother walked on ice that broke. How arbitrary safety was. How beauty and terror lived as neighbors in the same white field.

He kept the singing to himself. Who would believe the ice made music before it made death?

The brush trembled in his hand, leaving an unintended mark on canvas. Friedrich stared at it. Dresden, 1810. The studio windows let in northern light that fell across half-finished landscapes.

"This won't do," he muttered. Twenty-three years since the ice, and still his hand shook when certain memories surfaced.

The painting before him showed a monk standing on a shoreline, facing an emptiness of sea and sky. No boats, no birds, no comfort of scale or perspective. Just human smallness against natural immensity.

His patron had wanted something "uplifting." Friedrich almost laughed at the thought. He painted what lived inside him—vast silences, impossible distances, the human form always tiny before nature's indifference.

He never painted ice directly. Never the moment of breaking, never the red cap floating briefly on black water. Yet ice lived in every canvas—in the crystalline quality of light, in horizons that offered no rescue, in figures forever separated from what they contemplated.

"You always paint men from behind," his friend Dahl once observed. "Why never their faces?"

Friedrich had looked away. How explain that he couldn't bear to invent expressions for what had no adequate expression? That turning his figures away wasn't stylistic but necessary?

The face he couldn't paint was Johann's. The face reflected in every lake, every sea, every surface of his work was the one that disappeared beneath broken ice with words Friedrich couldn't hear.

Caroline began as a model and became his wife. She possessed a stillness he needed, an ability to stand motionless before windows for hours while he worked.

"What do you see out there?" he asked once.

"The river," she said. "The light on water."

Friedrich nodded. She understood without understanding. Saw without knowing all she saw.

Dresden, 1822. Morning light fell through tall windows of their apartment. Caroline stood looking out toward the Elbe, her back to Friedrich, her form silhouetted against the brightness.

He had avoided domestic scenes. His work lived in wild places, on mountains and shorelines where human presence seemed accidental and temporary. But something in this moment arrested him—the frame of the window holding both Caroline and the living water beyond, the light touching her through glass.

The composition arranged itself without effort. Figure before window before river before sky. Boundaries within boundaries, frames within frames. The window's geometry contained the river's fluidity just as painting contained feeling.

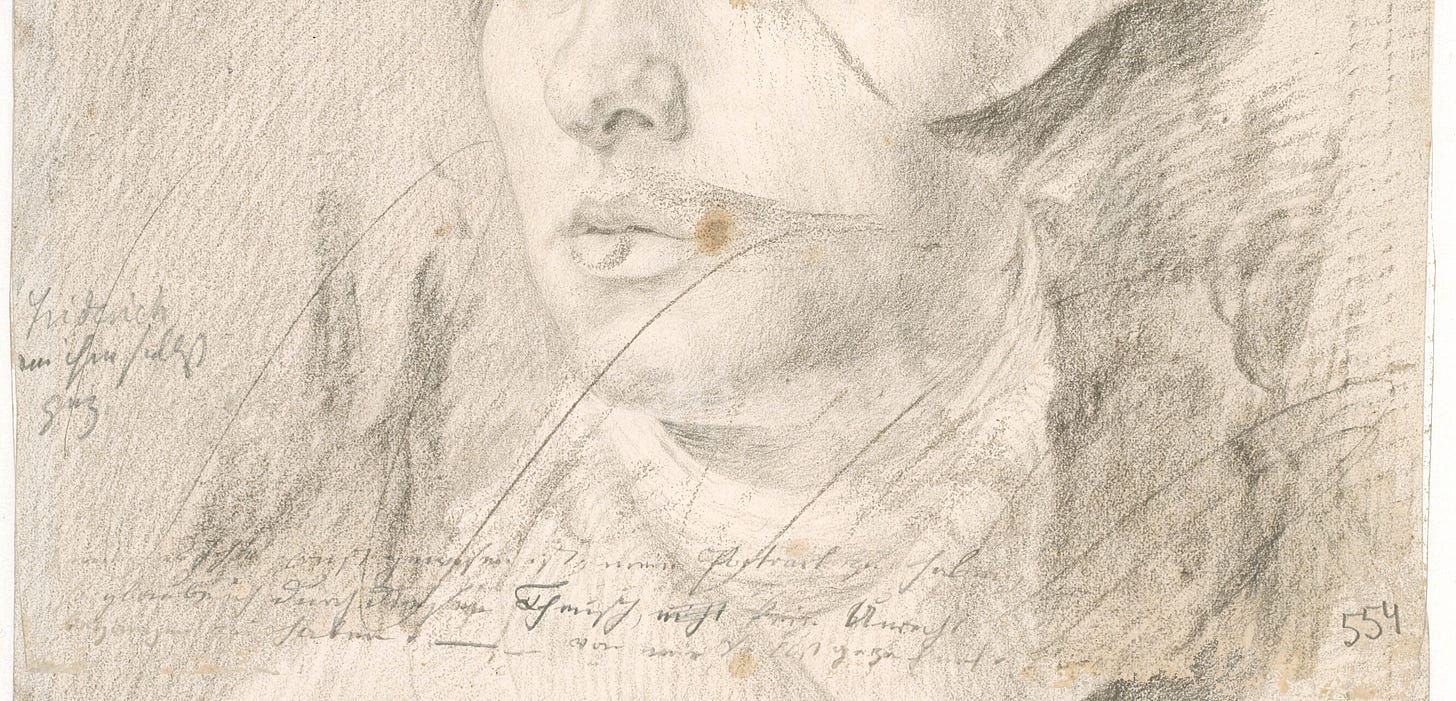

"Don't move," he said, reaching for paper to sketch.

She remained still, practiced in the art of becoming image. He drew quickly, capturing not just her outline but the quality of attention in her posture.

Water. Always water in his work, but never like this. Not frozen in threat but flowing in possibility. Not claiming life but supporting it. The Elbe moved past their window every day, constant yet never the same river twice.

As he sketched, Friedrich felt something shift. The ice that lived in memory, in muscles, in dreams—it didn't vanish, but its grip loosened. Caroline before the window, light touching her through glass, the river beyond moving freely—this was another kind of truth.

He had spent his life painting absence. Perhaps he could also paint presence.

The canvas emerged slowly over weeks. "Woman at a Window." Caroline in her blue dress, standing where boundaries dissolved. Interior and exterior. Human and natural. Containment and flow.

Unlike his vast landscapes, this painting created intimacy. The viewer stood not at abyssal distance but just behind Caroline, sharing her contemplation, almost close enough to touch her.

"It's different from your other work," Caroline said when he showed her the finished piece.

"Yes." He couldn't explain how. Words failed where painting spoke.

The blue dress echoed the river beyond the window. The light that touched her face was the same light that moved across water. The window frame that seemed to separate inside from outside actually united them in a single composition.

Friedrich stepped back, studying what he had created. The painting contained no obvious trauma, no desperate sublimity, no human insignificance before natural power. Yet Johann was there too—not in frozen absence but in living presence, in the light that connected all things, in water that moved freely rather than fixed in deadly solidity.

He had not painted grief directly. Had not shown ice breaking, a boy drowning, a red cap floating on black water. Instead, he had painted its opposite—connection where he had experienced severance, warmth where he had known cold, flow where he had confronted fixity.

Time moved differently in the studio. Hours compressed into moments of perfect focus or expanded into struggles with a single brushstroke. Friedrich lost himself in work when the exterior world grew too loud or too empty.

The Dresden years flowed. Marriage. Recognition. The slow waning of popularity as tastes changed. Always, the ice lived within him—not just memory but presence, a lens through which he saw everything.

His landscapes grew more extreme. "The Sea of Ice" showed a shipwreck crushed between massive ice floes, jagged shards rising like monuments to destruction. No human figures survived, only broken human endeavor. Critics found it too bleak, too unresolved.

They didn't understand. Resolution wasn't possible or even desirable. The ice would always break. The distance would always remain unbridgeable. What mattered was bearing witness to both beauty and destruction without looking away.

Yet "Woman at a Window" hung in their bedroom, a private counterpoint to his public work. On dark nights when old dreams returned—of reaching for Johann, of ice that sang before breaking—Friedrich would light a candle and look at Caroline framed against the living water beyond glass.

This too was truth. Not despite the ice but alongside it.

The stroke came in 1835. Partial paralysis, right side useless, painting nearly impossible. The great Friedrich reduced to small watercolors executed with his left hand.

Art fashions changed. His work disappeared into storage rooms. When visitors came, they spoke of him in the past tense even while he sat among them. Was a great painter. Created important works. As if death had already claimed him.

Caroline arranged his chair near the window each morning. The same window from the painting, though age had changed them both. The Elbe still flowed beyond glass. Light still fell through clear boundaries to touch what lived within.

Friedrich watched the changing light, the moving water. His paralyzed hand rested in his lap, fingers curled like a question mark. The painting hand, now still. The ice within him, temporarily thawed.

On his last good day, a young artist visited, eager to meet the forgotten master. The young man asked earnest questions about technique, about transcendence, about truth in art.

"What is the most important quality for an artist?" he finally asked.

Friedrich considered. The ice sang briefly in memory.

"Attention," he said.

"To technique? To composition?"

"To what breaks and what remains."

The young man looked confused but wrote it down dutifully. Friedrich turned back to the window, to light on moving water. The visitor soon left, disappointed perhaps to find an old man who spoke in riddles rather than the visionary he had expected.

After he was gone, Caroline brought tea.

"What did you mean—what breaks and what remains?" she asked.

Friedrich watched the river. Ice had once claimed his brother in water exactly that color. Yet here was water again, flowing free. Here was light again, touching everything equally. Here was the window, both boundary and connection.

"Johann is gone," he said, speaking his brother's name aloud for the first time in decades. "The ice broke. He remains."

Caroline's hand found his shoulder.

"The paintings remain," she said.

Friedrich nodded. "The paintings. The light. The attention."

He had spent his life transforming ice into image. Not to master memory but to honor it. Not to resolve grief but to inhabit it fully. The broken ice that claimed Johann had shattered something in Friedrich that never fully healed. But through that very brokenness, light entered differently.

Outside, the Elbe caught afternoon sun, water moving in patterns never the same twice. Inside, the old painter watched with complete attention, seeing both what was before him and what lived within—not as separate realities but as a single, flowing truth.